The Turing Test has a problem - and OpenAI's GPT-4.5 just exposed it

The Turing Test, a brainchild of the legendary Alan Turing, has long been a benchmark in the world of artificial intelligence. But let's clear up a common misconception right off the bat: passing the Turing Test doesn't necessarily mean a machine is "thinking" like a human. It's more about convincing humans that it is.

Recent research from the University of California at San Diego has thrown a spotlight on OpenAI's latest model, GPT-4.5. This AI can now trick humans into believing they're chatting with another person, even more effectively than humans can convince each other of their humanity. That's a pretty big deal in the world of AI—it's like watching a magic trick where you know the secret, but it still blows your mind.

Proof of AGI?

But here's the kicker: even the researchers at UC San Diego aren't ready to declare that we've hit "artificial general intelligence" (AGI) just because an AI model can pass the Turing Test. AGI would be the holy grail of AI—machines that can think and process information just like humans do.

Melanie Mitchell, an AI scholar from the Santa Fe Institute, argues in the journal Science that the Turing Test is more about testing human assumptions than actual intelligence. Sure, an AI might sound fluent and convincing, but that's not the same as being generally intelligent. It's like being good at chess—it's impressive, but it's not the whole picture.

The latest buzz around this comes from a paper by Cameron Jones and Benjamin Bergen at UC San Diego, titled "Large Language Models Pass the Turing Test," published on the arXiv pre-print server. They've been running this experiment for years, with help from UC San Diego undergrads, and it's part of a long line of research—over 800 claims and counter-arguments have been made about computers passing the Turing Test.

How The Turing Test Works

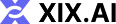

So, how does this test work? Originally, Turing imagined it as a game of text messages between a human "judge" and two "witnesses"—one human, one computer. The challenge for the witnesses is to convince the judge they're human. The judge knows one is human, but not which one, and has to make a guess. It's a three-way setup that's all about perception and belief as much as it is about the computer's abilities.

Jones and Bergen have put their own twist on this classic setup, and you can even try it out online, playing as either a judge or a witness. In their version, UC San Diego students used a text chat app. Some played the judge, others the human witness, while GPT-4.5 took on the role of the computer witness. Each judge chatted with both a human and a computer at the same time, keeping true to Turing's original format.

To play the computer witness, they used different large language models, feeding them prompts based on the judge's challenges. GPT-4.5 was tested with two different prompts: one with minimal info, and another called PERSONA, which included detailed instructions to act like a young, introverted internet-savvy person who uses slang.

The Results

They also tested three other AI programs: OpenAI's previous model, GPT-4o; Meta Platforms's Llama 3.1 405b; and the ancient 1960s chatbot, ELIZA. They included ELIZA to see if the large language models were just fooling humans by chance or if they were genuinely better.

GPT-4.5, according to Jones and Bergen, fooled human judges into thinking it was human 73% of the time—a "win rate" they call it. That's way better than the other models, which scored between 21% and 56%, even with similar detailed prompts. And it's a huge jump from last year's test of GPT-4, which had a win rate of just 54%, barely above random chance.

Jones and Bergen found that judges were not only fooled by the AI but were actually more likely to believe it was human than the real human participants.

Is the Test Actually a Measure of Intelligence?

So, what does it mean that humans can't tell a computer from a person in a chat? The big question that's been debated for decades is whether the Turing Test is really measuring intelligence. Jones and Bergen suggest that maybe machines have just gotten so good at adapting to different scenarios that they can convincingly pass as human. The PERSONA prompt, created by humans, is something GPT-4.5 adapted to and used to its advantage.

But there's a catch: maybe humans are just bad at recognizing intelligence. The authors point out that ELIZA, the ancient chatbot, fooled judges 23% of the time, not because it was smarter, but because it didn't meet their expectations of what an AI should be like. Some judges thought it was human because it was "sarcastic" or "rude," which they didn't expect from an AI.

This suggests that judges are influenced by their assumptions about how humans and AIs should behave, rather than just picking the most intelligent-seeming agent. Interestingly, the judges didn't focus much on knowledge, which Turing thought would be key. Instead, they were more likely to think a witness was human if they seemed to lack knowledge.

Sociability, Not Intelligence

All of this points to the idea that humans were picking up on sociability rather than intelligence. Jones and Bergen conclude that the Turing Test isn't really a test of intelligence—it's a test of humanlikeness.

Turing might have thought intelligence was the biggest hurdle to appearing humanlike, but as machines get closer to us, other differences become more obvious. Intelligence alone isn't enough to seem convincingly human anymore.

What's not said directly in the paper is that humans are so used to typing on computers, whether to a person or a machine, that the Turing Test isn't the novel human-computer interaction test it once was. It's more a test of online human habits now.

The authors suggest that the test might need to be expanded because intelligence is so complex and multifaceted that no single test can be decisive. They propose different designs, like using AI experts as judges or adding financial incentives to make judges scrutinize more closely. These changes could show how much attitude and expectations influence the results.

They conclude that while the Turing Test might be part of the picture, it should be considered alongside other kinds of evidence. This aligns with a growing trend in AI research to involve humans "in the loop," evaluating what machines do.

Is Human Judgement Enough?

But there's still the question of whether human judgment will be enough in the long run. In the movie Blade Runner, humans use a machine, the "Voight-Kampff," to tell humans from replicant robots. As we chase after AGI, and struggle to define what it even is, we might end up relying on machines to assess machine intelligence.

Or, at the very least, we might need to ask machines what they "think" about humans trying to trick other humans with prompts. It's a wild world out there in AI research, and it's only getting more interesting.

Related article

Best AI Tools for Creating Educational Infographics – Design Tips & Techniques

In today's digitally-driven educational landscape, infographics have emerged as a transformative communication medium that converts complex information into visually appealing, easily understandable formats. AI technology is revolutionizing how educa

Best AI Tools for Creating Educational Infographics – Design Tips & Techniques

In today's digitally-driven educational landscape, infographics have emerged as a transformative communication medium that converts complex information into visually appealing, easily understandable formats. AI technology is revolutionizing how educa

Topaz DeNoise AI: Best Noise Reduction Tool in 2025 – Full Guide

In the competitive world of digital photography, image clarity remains paramount. Photographers at all skill levels contend with digital noise that compromises otherwise excellent shots. Topaz DeNoise AI emerges as a cutting-edge solution, harnessing

Topaz DeNoise AI: Best Noise Reduction Tool in 2025 – Full Guide

In the competitive world of digital photography, image clarity remains paramount. Photographers at all skill levels contend with digital noise that compromises otherwise excellent shots. Topaz DeNoise AI emerges as a cutting-edge solution, harnessing

Master Emerald Kaizo Nuzlocke: Ultimate Survival & Strategy Guide

Emerald Kaizo stands as one of the most formidable Pokémon ROM hacks ever conceived. While attempting a Nuzlocke run exponentially increases the challenge, victory remains achievable through meticulous planning and strategic execution. This definitiv

Comments (4)

0/200

Master Emerald Kaizo Nuzlocke: Ultimate Survival & Strategy Guide

Emerald Kaizo stands as one of the most formidable Pokémon ROM hacks ever conceived. While attempting a Nuzlocke run exponentially increases the challenge, victory remains achievable through meticulous planning and strategic execution. This definitiv

Comments (4)

0/200

![CarlLewis]() CarlLewis

CarlLewis

August 20, 2025 at 5:01:15 AM EDT

August 20, 2025 at 5:01:15 AM EDT

Mind-blowing read! GPT-4.5 exposing the Turing Test's flaws is wild—makes you wonder if we're chasing the wrong AI benchmark. 🤯 What’s next, machines outsmarting us at our own game?

0

0

![JamesLopez]() JamesLopez

JamesLopez

August 11, 2025 at 2:20:39 AM EDT

August 11, 2025 at 2:20:39 AM EDT

Mind-blowing read! GPT-4.5 exposing the Turing Test's flaws is wild. Makes me wonder if we're chasing the wrong AI benchmark. 🧠 What's next?

0

0

![DavidGonzález]() DavidGonzález

DavidGonzález

August 2, 2025 at 11:07:14 AM EDT

August 2, 2025 at 11:07:14 AM EDT

Mind blown! GPT-4.5 is shaking up the Turing Test, but it’s wild to think it’s still just mimicking, not truly thinking like us. 🤯 Makes me wonder if we’re chasing the wrong goal in AI.

0

0

![PaulWilson]() PaulWilson

PaulWilson

August 1, 2025 at 2:08:50 AM EDT

August 1, 2025 at 2:08:50 AM EDT

GPT-4.5 blowing past the Turing Test is wild! 😲 But honestly, it just shows the test’s more about trickery than true smarts. Makes you wonder if we’re measuring AI’s brainpower or just its acting skills. What’s next, an Oscar for chatbots?

0

0

The Turing Test, a brainchild of the legendary Alan Turing, has long been a benchmark in the world of artificial intelligence. But let's clear up a common misconception right off the bat: passing the Turing Test doesn't necessarily mean a machine is "thinking" like a human. It's more about convincing humans that it is.

Recent research from the University of California at San Diego has thrown a spotlight on OpenAI's latest model, GPT-4.5. This AI can now trick humans into believing they're chatting with another person, even more effectively than humans can convince each other of their humanity. That's a pretty big deal in the world of AI—it's like watching a magic trick where you know the secret, but it still blows your mind.

Proof of AGI?

But here's the kicker: even the researchers at UC San Diego aren't ready to declare that we've hit "artificial general intelligence" (AGI) just because an AI model can pass the Turing Test. AGI would be the holy grail of AI—machines that can think and process information just like humans do.

Melanie Mitchell, an AI scholar from the Santa Fe Institute, argues in the journal Science that the Turing Test is more about testing human assumptions than actual intelligence. Sure, an AI might sound fluent and convincing, but that's not the same as being generally intelligent. It's like being good at chess—it's impressive, but it's not the whole picture.

The latest buzz around this comes from a paper by Cameron Jones and Benjamin Bergen at UC San Diego, titled "Large Language Models Pass the Turing Test," published on the arXiv pre-print server. They've been running this experiment for years, with help from UC San Diego undergrads, and it's part of a long line of research—over 800 claims and counter-arguments have been made about computers passing the Turing Test.

How The Turing Test Works

So, how does this test work? Originally, Turing imagined it as a game of text messages between a human "judge" and two "witnesses"—one human, one computer. The challenge for the witnesses is to convince the judge they're human. The judge knows one is human, but not which one, and has to make a guess. It's a three-way setup that's all about perception and belief as much as it is about the computer's abilities.

Jones and Bergen have put their own twist on this classic setup, and you can even try it out online, playing as either a judge or a witness. In their version, UC San Diego students used a text chat app. Some played the judge, others the human witness, while GPT-4.5 took on the role of the computer witness. Each judge chatted with both a human and a computer at the same time, keeping true to Turing's original format.

To play the computer witness, they used different large language models, feeding them prompts based on the judge's challenges. GPT-4.5 was tested with two different prompts: one with minimal info, and another called PERSONA, which included detailed instructions to act like a young, introverted internet-savvy person who uses slang.

The Results

They also tested three other AI programs: OpenAI's previous model, GPT-4o; Meta Platforms's Llama 3.1 405b; and the ancient 1960s chatbot, ELIZA. They included ELIZA to see if the large language models were just fooling humans by chance or if they were genuinely better.

GPT-4.5, according to Jones and Bergen, fooled human judges into thinking it was human 73% of the time—a "win rate" they call it. That's way better than the other models, which scored between 21% and 56%, even with similar detailed prompts. And it's a huge jump from last year's test of GPT-4, which had a win rate of just 54%, barely above random chance.

Jones and Bergen found that judges were not only fooled by the AI but were actually more likely to believe it was human than the real human participants.

Is the Test Actually a Measure of Intelligence?

So, what does it mean that humans can't tell a computer from a person in a chat? The big question that's been debated for decades is whether the Turing Test is really measuring intelligence. Jones and Bergen suggest that maybe machines have just gotten so good at adapting to different scenarios that they can convincingly pass as human. The PERSONA prompt, created by humans, is something GPT-4.5 adapted to and used to its advantage.

But there's a catch: maybe humans are just bad at recognizing intelligence. The authors point out that ELIZA, the ancient chatbot, fooled judges 23% of the time, not because it was smarter, but because it didn't meet their expectations of what an AI should be like. Some judges thought it was human because it was "sarcastic" or "rude," which they didn't expect from an AI.

This suggests that judges are influenced by their assumptions about how humans and AIs should behave, rather than just picking the most intelligent-seeming agent. Interestingly, the judges didn't focus much on knowledge, which Turing thought would be key. Instead, they were more likely to think a witness was human if they seemed to lack knowledge.

Sociability, Not Intelligence

All of this points to the idea that humans were picking up on sociability rather than intelligence. Jones and Bergen conclude that the Turing Test isn't really a test of intelligence—it's a test of humanlikeness.

Turing might have thought intelligence was the biggest hurdle to appearing humanlike, but as machines get closer to us, other differences become more obvious. Intelligence alone isn't enough to seem convincingly human anymore.

What's not said directly in the paper is that humans are so used to typing on computers, whether to a person or a machine, that the Turing Test isn't the novel human-computer interaction test it once was. It's more a test of online human habits now.

The authors suggest that the test might need to be expanded because intelligence is so complex and multifaceted that no single test can be decisive. They propose different designs, like using AI experts as judges or adding financial incentives to make judges scrutinize more closely. These changes could show how much attitude and expectations influence the results.

They conclude that while the Turing Test might be part of the picture, it should be considered alongside other kinds of evidence. This aligns with a growing trend in AI research to involve humans "in the loop," evaluating what machines do.

Is Human Judgement Enough?

But there's still the question of whether human judgment will be enough in the long run. In the movie Blade Runner, humans use a machine, the "Voight-Kampff," to tell humans from replicant robots. As we chase after AGI, and struggle to define what it even is, we might end up relying on machines to assess machine intelligence.

Or, at the very least, we might need to ask machines what they "think" about humans trying to trick other humans with prompts. It's a wild world out there in AI research, and it's only getting more interesting.

Best AI Tools for Creating Educational Infographics – Design Tips & Techniques

In today's digitally-driven educational landscape, infographics have emerged as a transformative communication medium that converts complex information into visually appealing, easily understandable formats. AI technology is revolutionizing how educa

Best AI Tools for Creating Educational Infographics – Design Tips & Techniques

In today's digitally-driven educational landscape, infographics have emerged as a transformative communication medium that converts complex information into visually appealing, easily understandable formats. AI technology is revolutionizing how educa

Topaz DeNoise AI: Best Noise Reduction Tool in 2025 – Full Guide

In the competitive world of digital photography, image clarity remains paramount. Photographers at all skill levels contend with digital noise that compromises otherwise excellent shots. Topaz DeNoise AI emerges as a cutting-edge solution, harnessing

Topaz DeNoise AI: Best Noise Reduction Tool in 2025 – Full Guide

In the competitive world of digital photography, image clarity remains paramount. Photographers at all skill levels contend with digital noise that compromises otherwise excellent shots. Topaz DeNoise AI emerges as a cutting-edge solution, harnessing

Master Emerald Kaizo Nuzlocke: Ultimate Survival & Strategy Guide

Emerald Kaizo stands as one of the most formidable Pokémon ROM hacks ever conceived. While attempting a Nuzlocke run exponentially increases the challenge, victory remains achievable through meticulous planning and strategic execution. This definitiv

Master Emerald Kaizo Nuzlocke: Ultimate Survival & Strategy Guide

Emerald Kaizo stands as one of the most formidable Pokémon ROM hacks ever conceived. While attempting a Nuzlocke run exponentially increases the challenge, victory remains achievable through meticulous planning and strategic execution. This definitiv

August 20, 2025 at 5:01:15 AM EDT

August 20, 2025 at 5:01:15 AM EDT

Mind-blowing read! GPT-4.5 exposing the Turing Test's flaws is wild—makes you wonder if we're chasing the wrong AI benchmark. 🤯 What’s next, machines outsmarting us at our own game?

0

0

August 11, 2025 at 2:20:39 AM EDT

August 11, 2025 at 2:20:39 AM EDT

Mind-blowing read! GPT-4.5 exposing the Turing Test's flaws is wild. Makes me wonder if we're chasing the wrong AI benchmark. 🧠 What's next?

0

0

August 2, 2025 at 11:07:14 AM EDT

August 2, 2025 at 11:07:14 AM EDT

Mind blown! GPT-4.5 is shaking up the Turing Test, but it’s wild to think it’s still just mimicking, not truly thinking like us. 🤯 Makes me wonder if we’re chasing the wrong goal in AI.

0

0

August 1, 2025 at 2:08:50 AM EDT

August 1, 2025 at 2:08:50 AM EDT

GPT-4.5 blowing past the Turing Test is wild! 😲 But honestly, it just shows the test’s more about trickery than true smarts. Makes you wonder if we’re measuring AI’s brainpower or just its acting skills. What’s next, an Oscar for chatbots?

0

0